Fenland Research, 8 (1993), 80-6.

On Middan Gyrwan Fenne: Intercommoning

around the Island of Crowland

In early May 1189 the abbot of Crowland put his fens in defence, that is, he closed them to all the livestock of the men of Holland, the communities to the north and east of the Fenland island of Crowland. He claimed this as customary and of his right, for the land had been granted to the monastery by King Æthelbald of Mercia (716-57), and the abbot usually closed it at that time of year to allow the grass to grow more freely. Although this was publicly proclaimed on the bridge at Spalding, the men of Holland, at the instigation of the prior of Spalding, an implacable rival of St Guthlac, refused to withdraw their animals, and when the abbot’s bailiffs began to impound their stock on the feast of Saints Nereus and Achilleus (12th May), they forcibly entered the marsh and occupied it. Elsewhere the fen had dried up and the surrounding communities were experiencing a shortage of pasture. That around Crowland was all that remained in the area, and the invasion thereof was an act of naked aggression prompted by greed and envy.

So the Crowland chronicler recorded the events (Riley 1854: 275-7). He recounts in considerable detail the complex legal battle that ensued but the case of the men of Holland is not put. Likewise, Crowland acted the innocent victim in 1206 when Peterborough Abbey made claim to marshes to the south of the river Welland, and it maintained its right in the face of concerted attempts to appropriate the fens to the north by the men of Deeping throughout the 13th century (Riley 1854: 311-5, 319-20). Crowland would appear to have been founded in a nest of vipers. However, the seeming aggressors probably had more reason than is at first apparent from the Crowland tradition. The process of reclamation only gathered pace after the Norman Conquest. It had begun as an essentially communal operation. Before large tracts of the waste were divided up between communities, the whole area had been intercommoned, that is it was used for pasture by all without any boundaries. The main stimulus to improvement was population growth and the process inevitably led to appropriation (HaIlam 1965: 3-39, 165). Elsewhere in the fens Crowland was not slow to take advantage of the opportunities offered to extend their demesnes, and it is probable that they attempted the same around Crowland. The men of Holland’s claim was almost certainly based upon their former rights of common in the unenclosed marsh.

Paradoxically, their case is eloquently expressed by the measures that Crowland took in its own defence: it protested too much. According to the abbey’s tradition, the two marshes of Goggisland and Alderland on either side of the Welland to the west of Crowland had been given to them by King Æthelbald on its foundation in 716, along with the island itself (Riley 1854: 5-8). There is no reliable evidence to substantiate this assertion and the most that can be said is that the abbey was established on a firm footing in the second half of the 10th century by Abbot Thurketel (Whitelock 1937: 175; Chibnall 1969: xxv-xxix). By the time of Domesday Book Crowland had amassed a sizeable endowment in Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire, Leicestershire, Huntingdonshire, and Cambridgeshire (DB i: 192d-193a, 204a, 222c, 231b, 346c). Unfortunately, however, the vill of Crowland itself is not described. The earliest evidence with some claim to independence from the abbey’s influence appears in the next century. King Stephen confirmed to the abbey the whole of the island and its two marshes, and its bounds are rehearsed in a single perambulation (WPC: f23d-25d; Riley 1854: 274-5). King Henry II issued a similar confirmation in 1171, and it was on the basis of this latter charter that Crowland claimed demesnal rights throughout the area.[81]

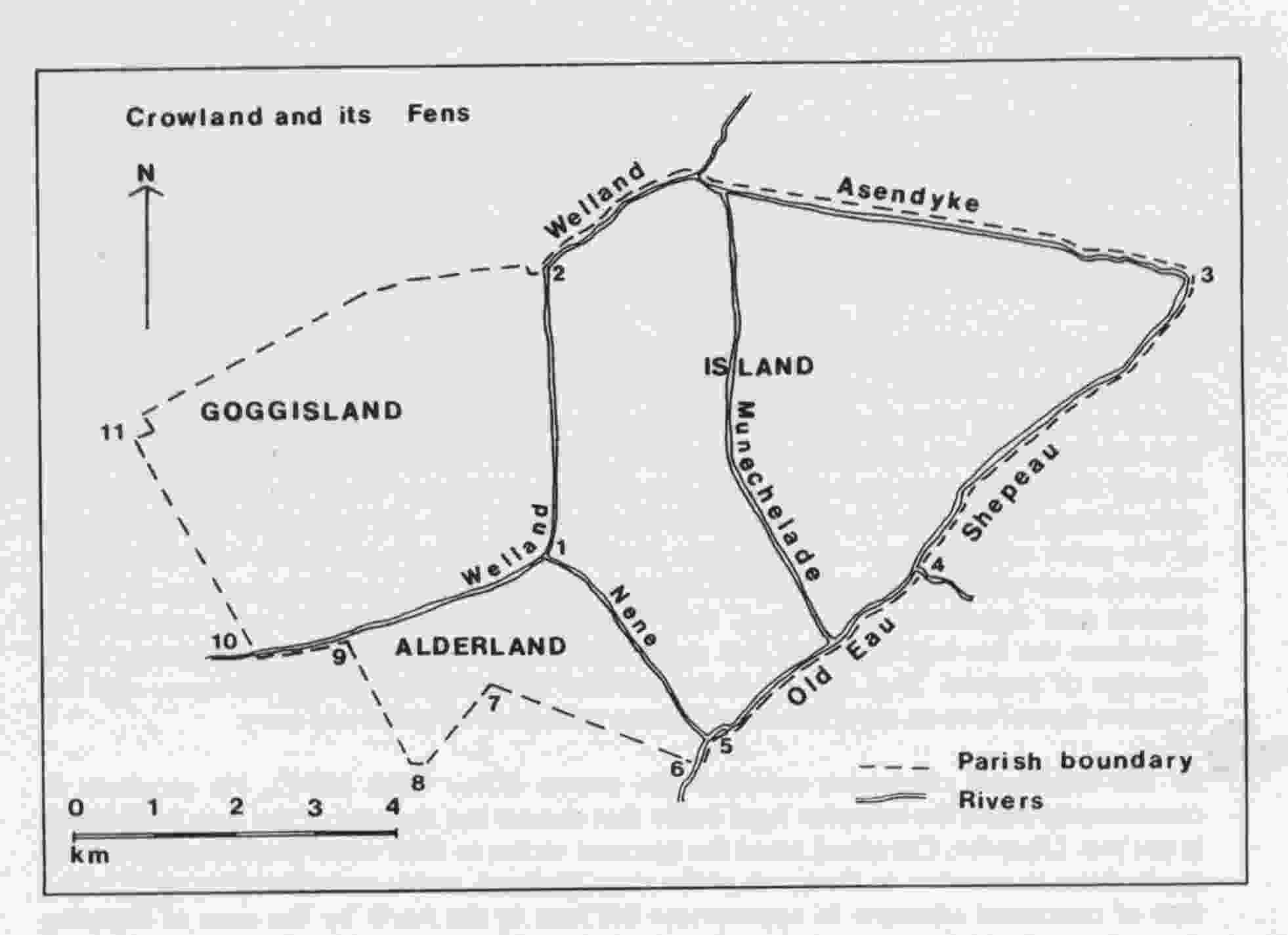

Figure 1 Crowland and its fens. Boundary markers: 1, Crowland Bridge; 2, Apynholt; 3,

Aswicktoft; 4, Tedwarthar; 5, Nomanesland; 6, Fynset; 7, Graynes; 8, Folwardstakes; 9,

Southlake; 10, Aspath; 11, Oggot

The apparent precinct can be located on the modern map with some precision, and it would appear that it substantially coincided with the area of the modern parish (fig. 1). But the implicit claims of the various invaders of St Guthiac’s patrimony belie Crowland’s assertion. The abbey’s account of the dispute makes it clear that the men of Holland did not originally make free of the whole of the abbot’s fen but merely occupied an area to the east of the significantly named Munechelade, ‘monks’s watercourse’ (Riley 1854: 281; Smith 1970: 8, 49). Since the abbot opposed them on the line of the Asendyke, this waterway can probably be identified with the present St James Drain which runs southwards from the confluence of the Welland and Asendyke to the Old South Eau. It was only subsequently that the rest of the marsh was appropriated consequent on a royal writ in the prior of Spalding’s favour (Riley 1854: 287). Likewise, the other claims were limited in extent. In 1206 the abbot of Peterborough substantiated his claim to Alderland as parcel of his fee, probably by right of his tenure of Borough Fen to the south, and secured the common of pasture in the area that his men had long enjoyed (Riley 1854: 31 1-12). Baldwin Wake and the men of Deeping were apparently similarly successful in asserting their rights to pasture in Goggisland, for in 1275 the fen was held by the abbey of Crowland of the Deeping fee (Riley 1854: 319; lllingworth 1812: 270).

This threefold division of the patrimony is reflected in what is perhaps the most infamous of Crowland sources. Sometime in the 14th or 15th century a monk of the house compiled the first part of the Historia Croylandensis claiming that it had been written by Abbot Ingulf in the late 11th and early 12th century (Riley 1854: 1-223; Searle 1894). Therein is contained a series of charters supposedly issued by various kings between 716 and 1048 in which the bounds of the abbey are detailed with some precision (Riley 1854: 5-8, 15-22, 24-31, 35-40, 65-72, 84-88, 129). In all but that of 833, in which the boundary of the sanctuary is [82] described, a distinction is drawn between the island of Crowland on the one hand and the two marshes on the other. The former extended from the bridge of Crowland by the Welland to the confluence of the Asendyke and thence to Aswickcroft, the present Aswick, where it turned south along Shepeau to the Old Eau and then to Nomanesland, and hence by the Nene to the bridge of Crowland. The bounds of the latter are described in two sections relating to the fens either side of the Welland. That on the south extended from Crowland Bridge by the Nene, the present Catswater Drain, to the Old Eau and followed the present parish boundary by various markers to the Welland and thence back to the bridge; that to the north went from the bridge to the Asendyke and thence followed the parish boundary to the west until it reached the Welland, again by various markers, and so returned to the bridge.

Heretofore these charters and their boundary clauses have been universally execrated (Sawyer 1968: nos 135, 162, 189, 200, 213, 538, 741, 965, 1049, 1294; Riley 1862: 32-49, 114-33). It cannot be claimed in any way that they are authentic Anglo-Saxon diplomas. They do not exhibit pre-Conquest diplomatic forms, the witness lists juxtapose individuals who were not contemporaries, and name forms are often wildly anachronistic. Much of the substance of the charters, namely the details of the estates granted and confirmed, is directly derived from a Crowland recension of the Domesday survey’s description of the estates of the abbey, here called ‘the Crowland Domesday’, in which information from a Domesday satellite has been incorporated (Riley 1854: 160-5; Roffe 1995). All of the charters were probably first composed before 1150, for none claims estates which were acquired after that date. Orderic Vitalis, who visited Crowland sometime between 1109 and 1124, possibly in 1119, was shown the charter of King Edgar and probably saw the Golden Charter, an 18th century facsimile of which seems to suggest that it was a 12th century production (Chibnall 1969: 342; Hickes 1703: 71). They would appear to have been composed between 1086 and 1124. However, the transmission of the charters before their incorporation in the Historia was complex, and it seems likely that the boundary clauses, in their present elaborate form, were later additions (Roffe 1995). In three of the charters the boundaries are first described in general terms by relation to the five rivers which surrounded the island, and this may represent an original feature of the charters (1). The more explicit clauses, however, are probably directly related to the various disputes in which the abbey was involved, for they neatly counter the various claims that were made.

The boundary clauses, then, provide a useful confirmation of the complexity of land rights in and around the island in the 12th century. They also enable us to perceive that the division were of some antiquity. The Welland and Crowland Bridge repeatedly appear as boundary markers. The Crowland Domesday of the Historia, which we must now accept as an authentic 11th century source, places Goggisland in Lincolnshire, but Alderland in Northamptonshire; the Welland and the Catswater remained the boundary between the two counties until the late sixteenth century (VCH Northants ii: 422; Nicolson 1988: 134-5)(2). In the East Midlands shires were no great respecters of estates and their limits; the shrieval system was essentially independent of such structures in that area, and settlements were regularly divided for apparently purely fiscal reasons (Roffe 1992: 32-42; Roffe 1986: 102-21). But in this instance a more ancient boundary seems to have been recognized. In what purports to be a charter of Edgar, Peterborough Abbey was granted the king’s tolls in the soke of Peterborough, and Crowland was noted as one of the points of collection (Sawyer 1968: no 787). Although a forgery, probably perpetrated by the monk Guerno in the 12th century, the substance of the reference is probably genuine (Hart 1966: no 15). Likewise, the boundary clause of the forged Peterborough charter of Wulfhere, which may relate to the 7th century estates of the abbey, follows the Welland and the Asendyke (Sawyer 1968: no 68; Potts 1974: 12-27).

Crowland would seem to have been a boundary foundation. As a monastery it was firmly in the Middle Anglian region. St Guthlac is said to lie ‘in the midst of the Gyrwe fen (on middan Gyrwan fenne)’ in a document known as ‘the resting places of the saints’ [83](Liebermann 1889: 9-19; Birch 1892: 24). The identification of the site by reference to a topographical feature suggests that the entry belongs to the earlier section that was composed by the late 9th century (Rollason 1978: 61-8), and as such it provides the only evidence independent of Crowland tradition of a pre-Danish foundation. In origin Crowland was almost certainly a cell of Peterborough. The charters are eloquent enough of Peterborough tradition, but earlier evidence also survives. Felix’s Life of Guthlac, an 8th century work, implicitly acknowledges the role of the great abbey. Guthlac made his profession at Repton, a daughter house of Medehampstede, the middle Saxon name of Peterborough, and his retreat to Crowland was apparently overseen by the extended community. Thus, it is recounted that a certain Tatwine rowed the saint to his new abode (Colgrave 1956: 88-9). This person is only identified as a local man, but it is unlikely that he was named gratuitously, for the name is rare and every character in the hagiography is introduced to make a point. It is therefore probably not coincidental that there was a priest called Tatwine at Breedon on the Hill, another cell of Peterborough, who was subsequently to become archbishop of Canterbury (Plummer 1896: 350), and it seems likely that he appears as some sort of representative of the abbey at the beginning of Crowland’s Christian history.

Peterborough Abbey may well have retained an influence in the affairs of Crowland until the 11th century, for, writing in the following century, Hugh Candidus asserted that the abbey had been held by the pluralist Abbot Leofric of Peterborough in 1066 (Mellows 1966:35). In this context, the possibility that the Asendyke boundary which was claimed as the limits of Peterborough in the Wulfhere charter must be treated with some reserve. The monastery might be expected to further its interests as far as it could, and it must be suspected from the evidence already cited that the notice of the river, to all appearances a post-Conquest cut, is a later interpolation into an authentic early clause. The Welland/Catswater line is probably more ancient, but it too is a canalization of uncertain date. Before the channels were cut through the gravel of the island, presumably to facilitate communications with an existing settlement in Crowland, the Welland skirted the island to west and north, and it is therefore likely that the area between the present Welland and Munechelade, the abbey’s undisputed demesne, represents the limits of the original precinct (Hayes & Lane 1992: 202)(3).

There is no comparable evidence to identify the territory to the north of this precinct before the claims of the men of Holland were made in 1189. But there is no reason seriously to doubt that it represents the land of the Spaldas which was assessed at 600 hides in the late 7th century assessment list known as the Tribal Hidage (Hart 1977: 44). Although the name is preserved in the place-name Spalding, doubt has been expressed about the habitability of the area in the early Saxon period (Davies & Vierck 1974: 253-7). However, recent archaeological survey has demonstrated occupation at the time (Hayes 1988: 321-6), and there seems no reason not to accept an identification which is congruent with the geographical structure of the Tribal Hidage and place-name evidence.

The claims of the men of Holland and the abbot of

Peterborough in the island of Crowland were evidently based on a long history.

A characteristic of tribal areas and regions was areas of pasture which were

common to all the communities that made them up (Jolliffe 1933: 54-6; Neilson

1920: xxxiii-lviii). Intercommoning practices of this kind were often the most

persistent institutional vestiges of such organization, frequently surviving

into the later Middle Ages. Given the ancient boundary along the Welland,

whatever its course, it seems highly likely that the aggression of the abbot of

Peterborough and the men of Holland was based precisely on such ancient rights.

Whether the claim to Goggisland by the lord of Deeping was similarly founded in

ancient usage is unclear. The western boundary of Crowland coincides with the

Holland/Kesteven boundary and this probably represents the 12th century line

alone the Midfendike and its continuation (Dugdale 1772: 194-5; Hallam 1965:

65). There is no evidence to indicate the antiquity of the line, but the

location of Deeping Fen within Holland may suggest that it was comparatively

late in date and [84]that the Welland

to Asendyke or beyond had formerly

constituted the boundary of a community to the east, possibly that

of the fen-edge tribe of the

Bilmingas.

It would seem, then, that the crisis that Crowland experienced in the 12th and 13th centuries was not merely prompted by the economic needs of the moment. It was symptomatic of more widespread changes in a society which was moving from a communal and tributary nexus to a seigneurial and manorialized one. There is no reason to doubt that the bounds of Crowland as expressed by the five rivers that surround the island represent some sort of ancient territory. Pre-Conquest monasteries frequently had an area of spiritual jurisdiction in which felons were free of the law in their immediate vicinity. But such sanctuaries were essentially independent of land tenure. Ramsey Abbey’s, for example, was not coincident with its demense (VCH Hunts ii: 187). Crowland’s rights in land were evidently limited. In a period of insignificant pressure on pasture intercommoning with other communities can have made little difference to Crowland’s economy. However, once fen began to be appropriated, the abbey must have experienced difficulties, and it felt it necessary to assert seigneurial rights. Already in the time of Abbot Geoffrey (1109-1124) ditches were scoured and it was no doubt at this time that boundary crosses were erected; St Guthlac’s Stone, the earliest surviving one, at Brotherhouse dates from this period (Raban 1977: 54). It had demonstrated the benefit of enclosing marsh in its Holbeach and Whaplode estates to the east (Raban 1977: 54), and it probably now attempted to convert vague rights of pasture into demesne within the island of Crowland itself. The challenge to its actions came in 1189 and the years that followed. In the event, the ancient rights of neighbouring communities, backed by the formidable support of their lords, prevailed.

Had Crowland had

stronger aristocratic backing it might have escaped the consequences of its

site and foundation. But it was a forlorn hope. The abbey probably recognized

its weak position. The charters set out the bounds of what it claimed in minute

detail, but its claim that Spalding Priory was a daughter cell appears tacitly

to accept the right of the communities to the north (Riley 1854:131-2).

Crowland must have had rights of common in the eastern part of Great Postland

Fen by virtue of its tenure of a berewick in Spalding (DB i: 346d), but it

could only claim exclusive rights by protesting its title to the whole

community. It also claimed a foothold in Deeping (Riley 1854: 20, 28, 69,87).

It failed. The quiet indignation of an unjustly treated community of monks of

the Historia is apparently a

self-serving sham.

Notes

1.

D. Stocker, (1993: 101-6) considers that the rivers only

became the boundary of the island after 12th century improvements. However, it

is clear that reclamation had not advanced that far by the time at which the

earliest of the surviving boundary crosses was made (Raban 1977: 54), and

Crowland tradition maintains that it was fen that was thereby defined. The

duplication of bounds in the charters does suggest the marrying of two distinct

sources

2. Alderland was adjudged parcel of the manor of Crowland in 1583

and transferred to Lincolnshire. As late as 1691, however, it was claimed as

part of Northamptonshire. The analysis here presented supersedes that in

Williams & Martin 1992.

3.

The high land of the island proper is to the west of

Munechelade. The reference to ‘monks’ in the name suggests an interest other

than the abbey’s in the area.

84

References

Birch, W. de Gray

(ed.). 1892. Liber Vitae: Register and

Martyrology of New Minster and Hyde Abbey. London.

Chibnall, M. (ed.).

1969. The Ecclesiastical History of

Orderic Vitalis ii. Oxford.

Colgrave, B. (ed.).

1956. Felix’s Life of St Guthlac. Cambridge.

Davies, W. & H. Vierck. 1971. The Contexts of the Tribal Hidage: Social Aggregates and

Settlement Patterns.

Fruhmittelalterliche Studien 8:

223-93.

DB. Domesday Book; seu Liber Censualis Willelmi Primi Regis

Angliae inter Archivos Regni in Domo Capitualari Westmonasterii

Asservatus. London 1783.

Dugdale, W. 1772. Imbanking and Draining. London.

Hallam, H.E. 1965. Settlement and Society: a study of the early

agrarian history of South Lincolnshire. Cambridge.

Hart, C. 1977. The

Kingdom of Mercia. In A. Dormer (ed.) Mercian

Studies: 43-62. Leicester.

Hayes, P.P..1988.

Roman to Saxon in the South Lincolnshire Fens. Antiquity 62:321-6.

Hayes, P.P. &

T.W. Lane. 1992. Lincolnshire Survey, the

South-West Fens. The Fenland Project No. 5/East Anglian Archaeology 55.

Hickes, C. 1703. Dc Antiquae Litteraturae Septentrionalis

Utilitate sive de Linguarum

Veterum Septentrionalium Usu Dissertatio

Epistolaris ad Bartholomaeum Shower.

Oxford.

lllingworth, W.

1812. Rotuli Hundredorum. London.

Jolliffe, J.E.A.

1933. Pre-Feudal England: the Jutes. London.

Liebermann, F.

(ed.). 1889. Die Heiligen Englands. Hanover.

Mellows, W.T. (ed.).

1966. The Peterborough Chronicle of Hugh

Candidus. Peterborough.

Neilson, N. (ed.).

1920. A Terrier of Fleet, Lincoinshire. London.

Nicolson, N. 1988. The Counties of Britain: a Tudor Atlas by

John Speed. London.

Plummer, C.

(ed).1896. Venerabilis Baedae Opera

Historica. Oxford.

Potts, W.T.W. 1974.

The Pre-Danish Estates of Peterborough Abbey. Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society 65: 13-27.

Raban, S. 1977. The Estates of Thorney and Crowland. Cambridge.

Riley, H.T. (ed.).

1854. Ingulph ‘s Chronicle of the Abbey

of Croyland. London.

Riley, H. T. 1862. The History and Charters of Ingulfus

Considered. Archaeological Journal 19: 32-49, 114-33.

Roffe, D.R. 1986. The Origins of Derbyshire. Derbyshire Archaeological Journal 106: 102-22.

Roffe, D.R. 1992.

Hundreds and Wapentakes. In A. Williams & G.H. Martin (eds): 32-42.

Roffe, D.R. 1995.

The Historia Croylandensis: a Plea

for Reconsideration. English Historical Review 110, (1995),

93-108.

Rollason, D. 1978. Lists of Saints Resting Places in

Anglo-Saxon England. Anglo-Saxon England 7:61-93.

Sawyer, P.H. 1968. Anglo-Saxon Charters: an Annotated Handlist

and Bibliography.

Searle, W.G. 1894. Ingulf and the Historia Croylandensis: an

Investigation Attempted. Cambridge.

Smith, A.H. 1970. English Place-Name Elements. Cambridge.

Stocker, D. 1993.

The Early Church in Lincolnshire: a Study of the Sites and their Significance.

In A. Vince (ed.) Pre-Viking Lindsey: 101-22.

Lincoln.

VCH Hunts. The

Victoria History of the County of Huntingdon. Eds W. Page, C. Proby, H.E.

Norris, S. Inskip Ladds. London.

VCH Northants. The

Victoria History of the County of Northampton. Eds W. Ryland, D.

Adkins, R.M.

Serjeantson. London.

Whitelock, D. 1937.

The Conversion of the Eastern Danelaw. Saga

Book of the Viking Society xii: 159-76.

Williams, A. &

G.H. Martin (eds). 1992. The Lincolnshire

Domesday. London.

WPC. Spalding

Gentlemen’s Society. Wrest Park Cartulary.

86