Sitting on the fence:

the Staffordshire Hoard find site in context

Haskins

Society Conference,

The

Staffordshire Hoard was found in 2009 by a metal detectorist just to the south

of

The hoard was found on the side of a

somewhat inconspicuous natural hillock in what had been before 1838 the

extra-parochial

For such a minor place, Ogley Hay is

relatively well documented. It is first recoded in an Anglo-Saxon charter of

994 in which Archbishop Sigerid confirmed to the

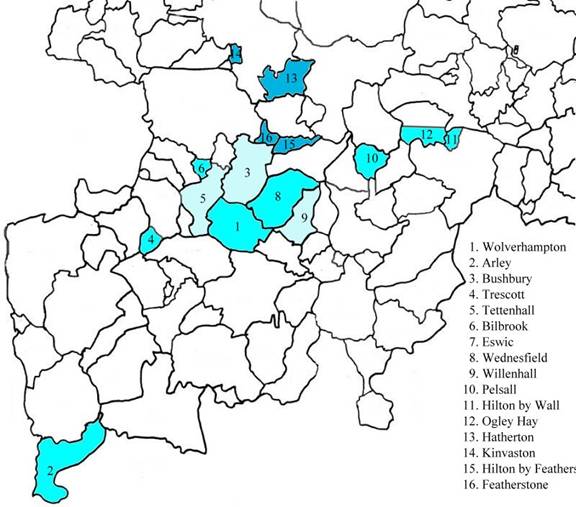

Figure

1: the estates of the

Now, if we follow the usual dictates

of landscape history, we would reconstruct an earlier estate by looking at the

extent of the parish of the main church associated with it. In

Figure

2: the parishes of

Re-foundation of earlier minster churches is not precluded, but the point here is that the ecclesiastical structures we see in the eleventh century and afterwards are an uncertain guide to the organization of territory before the Conquest. The interrelation of the estate with surrounding fees provides a better insight. We are used to the idea of estate formation in terms of the grant of compact parcels of land by charter or book. Booking, though, was not the only means by which the fees we see in Domesday Book came into being. The division of large complexes, so-called multiple estates, element by element is less prominent in the sources, probably largely because it created loanland rather than bookland. It is, nevertheless, an equally significant mechanism of estate formation. It can be widely detected in recurring patterns of lordship in which two or more lords each had a share in a series of divided or closely related vills. Such interlocking patterns provide invaluable clues to the history of the tenurial landscape before it is explicitly documented. In the fenlands of eastern England they have led to the identification of complexes that can be dated to the Middle Saxon period. Similar patterns are found around Wolverhampton and it is these that point to the earlier context of the Domesday manor and its soke.

The story is a complex one. Wolverhampton itself, along with Wednesfield, part of Willenhall, and possibly part of Bushbury formed a consolidated core. The remaining lands were detached. Arley, to the south-west, is remote from the estate structures around Wolverhampton and may be a stray addition to the fee. In 963 it was granted by King Edgar to his faithful minister Wulfgeat of Duddeston, in all likelihood a kinsman of Wulfrun. Eswic, probably somewhere in Kingswinford parish, may have had a similar origin. Neither exhibits suggestive interactions with surrounding estates. The other elements of the soke, however, are closely related to neighbouring fees.

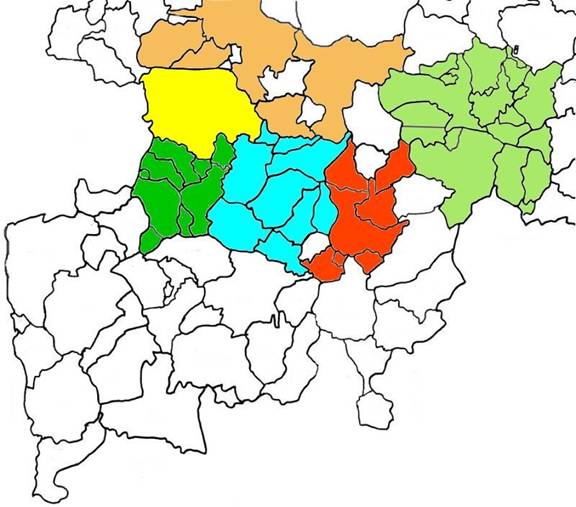

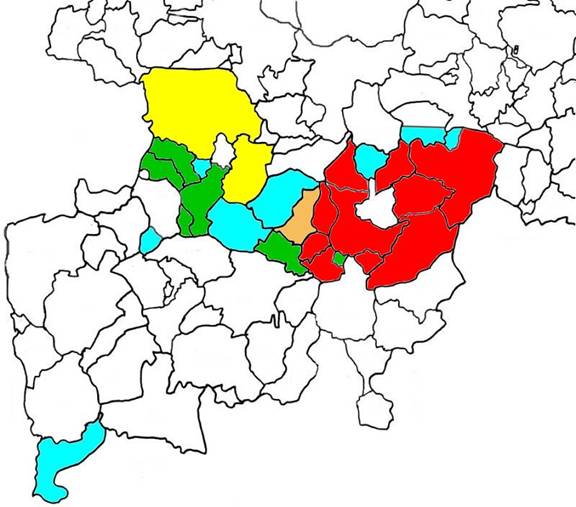

Figure 3: the Wolverhampton soke and its tenurial context

Pelsall, Ogley Hay, and Hilton by Wall are associated with the lands of Wednesbury to the east (figure 3, red). The manor of Wednesbury with its appendages was a royal manor in 1086 and apparently so in 1066. Of its members only Bloxwich and Shelfield, representing Walsall Wood, to east and west of Pelshall, are explicitly named, but others can be identified from later records. Walsall itself was the site of the church of the manor in the thirteenth century and the whole of the vill was held of the king and so it is likely to have been parcel of Wednesbury in 1086. Bentley was subsequently a royal sergeancy and so was probably also a member of the manor at the same time, while the tenurially related Darlaston may have had a similar status. None of these is named in the GDB text and so it is likely that they were either subsumed in the three hides assigned to Wednesbury itself or were geld free and therefore not described.

It is clear that the manor had also extended beyond the lands of the king before 1086. Aldridge, held by Robert d'Oilly of William fitzAnsculf at the time of Domesday was in the soke of the king and had been held by two thegns in 1066. Robert succeeded to many ministerial tenements after the Conquest and its seems likely that he did so here. He also held Aldridge’s chapelry of Great Barr, again of William fitzAsculf, and Shenstone of Roger of Montgomery. There is no indication of his office, but it was apparently real enough. By the 13th century all three settlements were in his honour of Hook Norton as was the manor of Wednesbury itself. Pelsall, Ogley Hay, and Hilton interlock with this complex.

Wolverhampton's land in Willenhall

(figure 3, tan) is close to Wednesbury and could conceivably have been part of

the manor sometime before the Conquest. The king's land in the same place,

however, was constituted as a second royal manor in 1086. As far as can be perceived, the

manor had no other members at the time, unless the thegnages in Bentley and

Darlaston belonged to it, but in the later Middle Ages it was represented by

the manor of Stow Heath which extended into Wolverhampton and Bilston. Again,

there is a degree of interlocking with the Wolverhampton fee.

Bilston

itself is described in Domesday as a separate tenement. It was also in the

hands of the king, but it was held as a member of the king’s manor of

Tettenhall (figure 3, dark green) rather than of Willenhall or Wednesbury. It

is this manor that provides a context for Wolverhampton’s lands to the west.

Bescot to the east of Wednesbury in the parish of Walsall belonged to the

manor, as did Compton, Wighwick, Codsall and Perton in the parish of

Tettenhall. Trescott can be said to be only geographically related to this

complex, but Tettenhall and Billbrook would seem to have been cut out of the

larger estate.

The tenements in Bushbury, Featherstone, and Hilton by Featherstone are not unequivocally related to any of these three royal manors. Much of Bushbury was in the hands of William fitzAnsculf. But there were various other interests, notably land that belonged to what was probably a comital estate in Essington to the north. Whatever its status, it was not the most substantial estate in the area. That was the bishop of Chester's manor of Brewood which abutted on Bushbury and Featherstone to the west. There is nothing to suggest a tenurial link in either 1086 or 1066 with either the Wolverhampton or Essington estates, but the place-name Bushbury, 'the bishop's settlement', strongly suggests a connection at an earlier date (figure 3, yellow).

The manor of Wolverhampton, then, was associated with four distinct tenurial complexes in 1086, namely the three royal manors of Wednesbury, Willenhall, and Tettenhall, and the manor of Brewood. This might seem to suggest that the complex had no identity earlier than the foundation of the church of Wolverhampton in the late tenth century. There are indications, however, that the three royal manors had always been closely associated. The identification of Bescot to the east of Wednesbuy as a member of Tettenhall is a straw in the wind here. It is an odd connection unless it represents an earlier structure. There are indeed other links. Bradley, for example, most likely a member of Wednesbury, was in the township of Wolverhampton in the middle ages. This is not necessarily an ancient feature but could, conceivably pre-date the hundred boundary that divides the two settlements. There are numerous other interconnections of this kind on both an administrative and ecclesiastical level.

But it is the place-names Wednesbury

and Wednesfield that

provide the most compelling evidence. Wednesbury means 'Woden's defended enclosure' and

Wednesfield 'Woden's open land'. The specific of both names, namely Woden', has

excited much comment as a marker of pagan survivals. But it is the generics,

bury and field, that interest us here. In estate terms they must indicate that

Wednesbury was a fortified nucleus in an estate called Wednesfield. There

is an elegant demonstration of the relationship in the earliest reference to Wednesfield.

Writing in the late tenth century and drawing on texts no longer extant,

Ealdorman Æthelweard recorded that in 910 the Danes were defeated by the

combined armies of Wessex and Mercia at Vuodnesfelda. John of Worcester

and the Annals of St Neots similarly identify the site of the battle as

Wednesfield. The other versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, by contrast, call

it Tettenhall. The disparity has provoked much discussion, with proponents of

both sites providing reasons for the notice of the other. But the apparent

contradiction is resolved if Wednesfield is understood as the estate

name and Tettenhall a place within it.

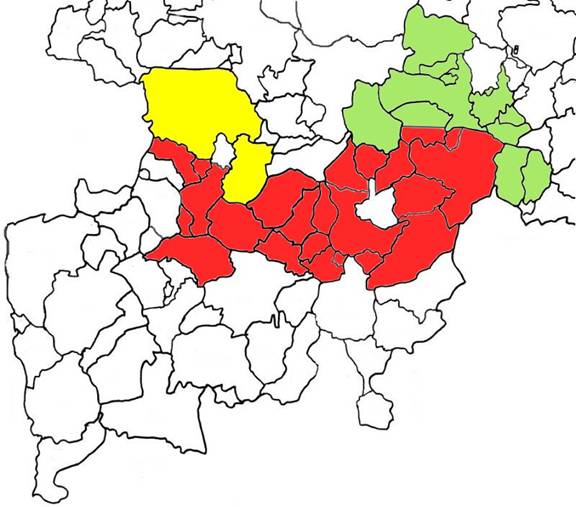

So, it can be tentatively concluded that that part of the Wolverhampton estate that approximated to a soke in 1086, including the site of the deposition of the Staffordshire Hoard, was granted out of a royal estate called Wednesfield. The lands associated with the three royal manors in 1086 define its minimum extent (figure 4, red). It would appear to have extended further south in the tenth century, for the bounds of Wolverhampton, as recorded in a charter of 984, included Upper Penn. The boundary to the north is more clearly defined. Bushbury, 'the bishop's defended enclosure', may well have been named in apposition to the king's enclosure in Wednesbury and so the Brewood complex would mark the limits of Wednesfield to the north west (figure 4, yellow). Further east Watling Street, recorded as the northern limit of Ogley Hay in the 994 charter, was the boundary between the king's land and that of the church of Lichfield (figure 4, light green), possibly with the place-name Norton in Norton Canes, 'the northern settlement', t the west of Ogley Hay, memorializing it. More certainly, Little Aston, 'the eastern settlement', in Shenstone parish marks the eastern boundary.

Figure

4: the royal estate of Wednesbury

The dating evidence, such as it is, does not go much beyond 910. But it is likely that even then there was already a long history of royal administration in the area. Thus, in 733 King Æthelbald of Mercia granted to Mildrith, the abbess of Minster-in-Thanet, and her familia the remission of the toll due on one ship at London, in loco qui dicitur Willanhalch. Willenhall was clearly a royal vill, or part of one, in the eighth century. Unfortunately, there is little early documentation for the Lichfield estates, but the reservation of ecclesiastical dues throughout the fee, both through extended parishes and the right to advowsons, is striking. The close match of secular with spiritual rights suggests that the complex was early, possibly even going back to the foundation of the church in the seventh century or before.

Given the nature of the limited sources, inevitably much of this is best guess. Nevertheless, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that Ogley Hay had been granted out from the periphery of what had long been a royal estate. This in its turn raises the possibility that the Staffordshire Hoard was deposited in the king's land close to a major boundary. The fact in itself, of course, might be taken to underline just how marginal the site was. But it resonates with two further characteristics that point in a different direction. We have already noticed in passing that Ogley Hay was extra-parochial. It stood outside of the network of vills that made up the infrastructure of local government at its lowest level. Significantly, it was also intercommoned by communities to the east and across the boundary to the north. Such a profile is typical of sites that were used as communal meeting places.

Could Ogley Hay also be an example? There is, of course, no record of a meeting place. But the place-name Shire Oak occurs just under a mile to the south-west of the find-site. The Reverend Stebbing Shaw, writing in 1801, explained it thus:

Shire Oaks is the name of a farm upon the summit of a

hill so called, lying to the great roads from Lichfield and Shenston (which

here unite), towards Walsall. A large oak in the valley, a quarter of a mile

from this farm, separates Shenston from Walsall, or Walsall wood, and is named

Shire Oak, from the word Scyre, to divide…

The farm was located just south of where the Shire Oak pub is now (figure 5). The site of the tree was down the hill to the west. Neither Shire Oaks Farm nor Shire Oak was within the bounds of Ogley Hay as mapped in the nineteenth century. However, it is possible that one or both were at an earlier date. Unfortunately, apart from Watling Street, the waypoints of the OE charter bounds of 994 are too vague to trace on the ground today with any confidence. But a perambulation of 1300 reveals that Ogley Hay extended further to the west and south than later, although the exact line of the boundary cannot be determined.

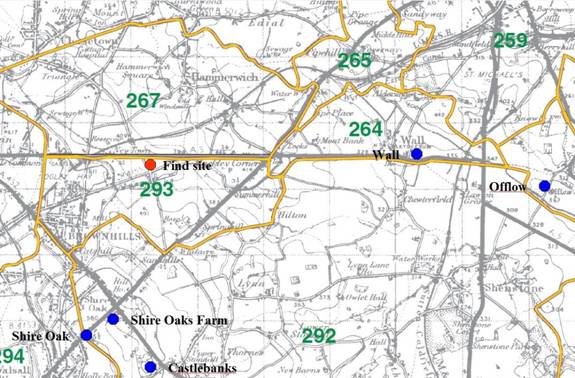

Figure 5: meeting places close to Ogley Hay

If it did not include Shire Oak and Shire Oaks Farm, then Ogley Hay abutted thereon. Either way, the association is of some considerable interest. Old English scir, as Shaw devised, connotes a division and the linking of the term with a specific tree must suggest that it was a meeting place. The earliest reference to Shire Oak dates from 1533, but neither then nor at any time in the Middle Ages did the county court meet there. Staffordshire, which came into existence sometime in the tenth century, always seems to have met in Stafford. The shire in question, then, was most likely an earlier Anglo-Saxon institution. 'Small shires' of this kind, encompassing areas as extensive as Wednesfield as reconstructed here and the lands of Lichfield, are well attested in the North and sporadically elsewhere in pre-Conquest England.

I suspect, then, that Ogley Hay was less remote than it has always seemed. It may well have been economically marginal, but it seems to have occupied a prominent place in a mental landscape. And that mental landscape may have been of long standing when the hoard was deposited. Immediately to the south of the site of Shire Oaks Farm is Castlebanks, an Iron Age hill fort and, presumably an earlier communal focus. Two and a half miles to the east is Wall, the site of the Roman town Letocetum, while a mile further east was the meeting place of Offlow Hundred just north of Watling Street in Swinfen. Do we see here a sequence of successive folk assemblies? We may well do so.

Now comes the difficult part. What

does this tell us about the Staffordshire Hoard? Well, it is still possible

that the site is completely contingent. It may just have been a convenient spot

to hide a vulnerable stash. But our analysis makes this, the Fargo option, open

to question. The tentative identification of the Ogley Hay area as a place of

symbolic importance within a wider tenurial landscape provides a context for

the ritual interpretation that its composition has suggested to many. The

Beowulf scenario is a possibility. Others remain. For my part, I am agnostic

and so, like the Staffordshire Hoard itself, I am going to sit on the fence.

©David Roffe 2014